Chapter 2 Gravity and Dark Matter

2.1 The Two Body Problem

Kepler stated three laws of planetary motion:

-

planets move on ellipses with the Sun at one of the foci

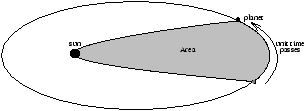

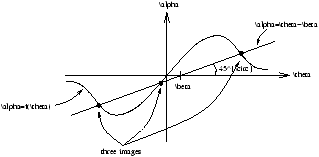

- the area swept out in a unit amount of time by the line joining the Sun to the planet is constant

Figure 2.1 - Kepler's Second Law

- T2=ka3 where T is the orbital period, a is the average distance from the Sun and k is some constant

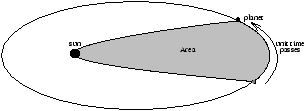

The general two body problem solves for the motion of two masses under their mutual gravitational interaction for arbitrary values for m1 , m2 , r1(0) , r1(0) , r1(2) and r2(0) .

2.1.1 General Coordinate Consideration

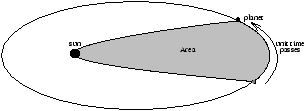

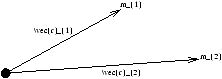

Figure 2.2 - Gravitational Force Between Two Bodies

there is no net force as

F=F12+F21=0=m1r1+m2r2

which we integrate to form

m1r1+r2=c

and again

m1r1+m2r2=Ct+D=(m1+m2)rC

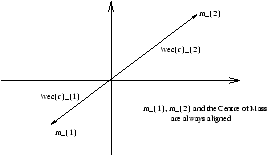

therefore the centre of mass defines an inertial frame which refers the centre of mass frame which sets

C=D=0

Þ m1r1+m2r2=0

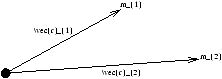

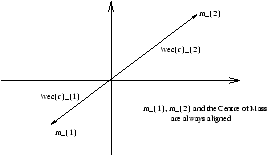

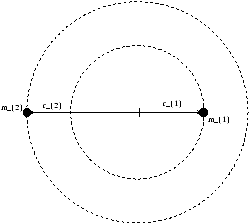

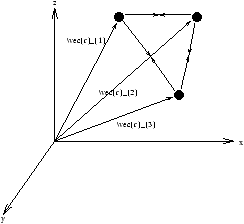

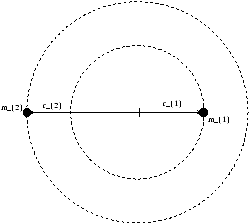

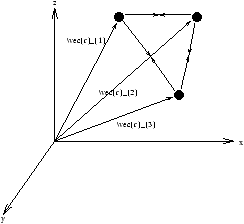

Figure 2.3 - The Centre of Mass Frame

In addition the motion is confined to a plane which is defined by r1(0) and r1(0) .

Figure 2.4 - Motion Confined to a Plane

we now consider that the motion of m2 is

we know that

and so we can rewrite our previous equation as

so we can say that

and we find the acceleration is

similarly this can be found for m1

where

2.1.2 General Solution for Circular Orbits

| a=r1+r2=r2 |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

+1 |

ö

÷

÷

ø |

=r2 |

|

2.1.3 Applications of Circular Orbits and Solutions

Visual Binaries

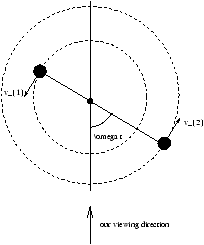

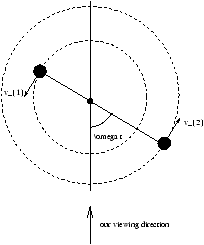

The ideal case for a Visual Binary Orbit is in the plane of the sky

Figure 2.5 - A Visual Binary Orbit System

we measure r1 , r2 and T so that we can work out

and also that

which provides us with two simulateous equations which permits us to calculate m1 and m2 .

2.1.4 Spectroscopic Binaries

Spectra of Both Stars Measureable

Initially we will be assuming that the plane of orbit is edge on so we observe the full componment of radial motion. This is where the inclination is 90°

m1r1+m2r2=0

m1r1+m2r2=0

m1v1=m2v2

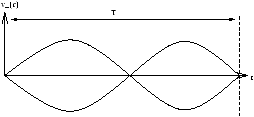

Figure 2.6 - Our View of the Remote System

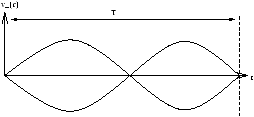

we measure the radial velocities

Figure 2.7 - The Radial Motion of the System

now

now using Kepler's Third Law

now by combining our results of the above and m1v1=m2v2 we obtain an equation that allows us to obtain the mass of the stars

However if the plane of orbit is inclined at an angle i then we only measure

v1sini=v1'

v2sini=v2'

where we only can measure v1' and v2' . Therefore we get

but if i is unmeasureable there is an uncertainity of sin3i in the measurement of the masses.

In eclipsing binaries we know that sini~ 1 .

Only One Spectrum is Visible - Planet Finding

The first planet discovered was by Mayor and Queloz (1995 - Nature 378,355). From the previous subsection

m1v1=m2v2

m1v1'=m2v2'

and rearranging this gives

The Right Hand Side of the above equation is the observarable part of the mass function. This is currently the best method for detecting planets. From spectroscopy we can determine the type of star and hence its mass ( m1 ). For planets m2<<m1 so

The Left Hand Side is what that can be determined.

Considering the detectability

If we take Jupiter as an example

T=11.9 years

m2=1.90× 1027kg

v1'=12ms-1

Jupiter is just detectable as the current limit is about 10ms-1 for v1' .

Solution of the General Two Body Problem

Acceleration in Plane Polar Coordinates

Motion is confined to a plane so it is sensible to use the plane polar coordinate system.

Figure 2.8 - Acceleration in Plane Polar Coordinates

we now use the unit vectors lr and lq as the unit vectors in the radial and tangential directions.

r=rlr

Þ r=rlr+rlr

we now look at the change in the unit vector

Figure 2.9 - Considering the Change of The Unit Vectors

differentiating again

where (r-rq2)lr is the radial acceleration and (2rq+rq)lq is the tangential acceleration.

By applying this we can get the equations we need to solve for our two body problems

By using Kepler's Second Law we start off with

rq+2rq=0

and we integrate

r2q=constant=h

however

r2q=2× (rate of sweeping)

Figure 2.10 - ???

this is a result of the central force, which leads to the result of Kepler's Second Law.

Another view would be to introduce h

h=r×r

differentiating this gives us

mh=0

mh=constant=mr×r=L=angular momentum

or this can be interpreted that Kepler's Second Law just states that angular momentum is conserved.

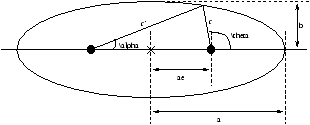

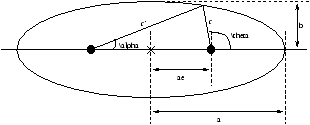

Ellipse in Plane Polar Coordinates

in cartesian coordinates an ellipse is

an ellipse is a locus of points such that the sum of the distance to the two foci is fixed. An ellipse can be fully specified by two numbers.

Figure 2.11 - An Ellipse

where a is length of the semi-major axis ( b is the semi-minor axis) and e is the eccentricity.

r+r'=2a

r+r'=a-ae+a+ae

rcosq+2ae=r'cosa

rsinq=r'sina

r2cos2q+4a2e2+4aercosq+r2sin2q=r'2

r'=2a-r

r'2=4a2-4ar+r2

r2cos2q+4a2e2+4aercosq+r2sin2q=4a2-4ar+r2

however r2=r2sin2q+r2cos2q so

4a2e2+4aercosq=4a2-4ar+r2

recosq+r=a(1-e2)

in general e can be greater than one which makes the ellipse equation form a conic section.

Figure 2.12 - Conic Sections

The closest approach where q =0 then r=a(1-e) which is known as the perigee. The furthest approach where q =p is where r=a(1+e) is known as a apogee. This leads to b=a(1-e2)1/2 .

The General Solution and Kepler's Third Law

| |

é

ê

ê

ë |

eg. for r2, M'= |

|

ù

ú

ú

û |

r2q=h

we write this as

we use the substitution u=1/r and also conservation of angular momentum dq/dt=h/r2=hu2

we differentiate once

and then differentiate again

| |

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

= |

|

=-h |

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

=-h |

|

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

We need two equations

-

at=-GM1M2/2E (Problem Sheet 1, Question 6)

where at=a1+a2

- GM'/h2=1/a(1-e2)

now the total angular momentum is

L=m1h1+m2h2=m1r12q+m2r22q

by using m1r1=m2r2 the second equation can be tidied up after lots of crunching to obtain

now by using the first equation we get

for a given L and E we can compute at and e , for example

and the orbit is

We notice that when E=0 that at=¥ and e=1 so when E<0 then e<1 occurs and we get a bound orbit (ellipse/parabola). However when E>0 then e>1 and so we have a unbound orbit which is a hyperbola.

General Form of Kepler's Third Law

The area of an ellipse is

the rate of sweeping is

by squaring the rate of sweeping we get

for example for r2

this can be manipulated to obtain

This is Kepler's Third Law in its general form.

2.2 Galaxy Rotation Curves

The sun rotates around the centre of our galaxy, the Milky Way, at about r=8.5 kpc and speed vc=220kms-1 (which is the circular speed). In the Milky Way the circular speed is approximately constant with radius. In other large spiral galaxies the rotation curve is approximately flat and can be measured well beyond the extent of the optical light ( ~ 10kpc ) with radio measurements ( ~ 40kpc ).

In we consider that the galaxies act like point masses we get

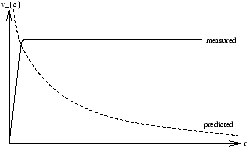

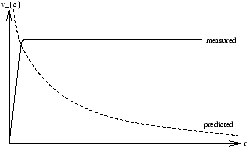

however a measurement of the mass gives figure 2.13

Figure 2.13 - Measured/Predicted Mass Distribution of a Galaxy

Figure 2.13 shows us that most of the mass cannot be concentrated neat the galaxy centre even though most of the light is within 10kpc . A more sophisticated model is the stella light method

a typical rs is 3kpc . Computing vc for this mass distribution it peaks at 2.2rs , beyond 3rs the point mass model is good enough.

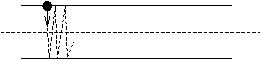

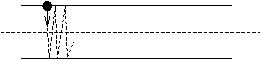

Another technique to measure the mass of points on a galaxy is to look at the oscillating acceleration of the stars, their vertical motion, as in figure 2.14

Figure 2.14 - Vertical Oscillating Acceleration

If there is more mass in the section of the disk then the acceleration of the stars on the top/bottom of the galaxy is much greater. This is the basis of calculating the mass at certain points through the galaxy. If this is done then we it tells us that what we see makes up the galaxy is what is there.

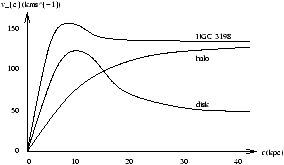

So we postulate a dominant spherical distribution of dark matter (of unknown form) to explain the rotation curve. What is r (r) for the galaxy? For a spherical distribution only M(<r) has gravitational effect and so acts as if at r=0 .

| M(<r)= |

ó

õ |

|

r (r')rp r'2dr' |

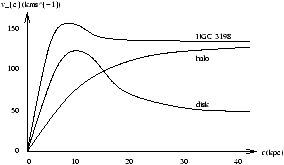

Figure 2.15 - NGC3198

The disk mass, computed from the light, is about 3.4× 1010M . Because for the halo

therefore the total mass inside r<30kpc is

| M(<30kpc)=Mdisk× |

|

=1.6× 1011M |

|

we recall for ??MW?? that Mstar~ 1× 1011M

within 100kpc we find that

so we can conclude that in spiral galaxies that most of the mass is in the form of dark matter. This matter is distributed with the density of

which out to the limits of measurement show that

since Mµ r we don't really know the masses or what their sizes are.

2.3 The Virial Theorem

For a planet in a circular orbit around a star

2T=-U

where T is the kinetic energy and U is the potential energy. More generally for a binary star

<2T>=-<U> (where <x> is average of x)

This is covered in Problem Sheet One, Question 7.

The Virial Theorem states for any gravitationally bound system in a steady state equilibrium then, then the time averaged kinetic energy is equal to minus the time averaged potential energy.

Þ <T>=-<U>

An alternative formalation of this is

E=T+U

so the total energy is half the potential energy.

The Virial Theorem is a powerful tool for measuring masses on different scales, from star clusters to galaxy clusters.

Consider a bound collection of masses, in an inertial frame where the centre of mass is stationary.

now

| 2T= |

|

mir |

i= |

|

|

(ri.mir |

i)- |

|

ri.miri |

To prove this we will consider three points

Figure 2.16 - The Appication of the Virial Theorem on Three Points

| |

|

ri.Fi=r1(F12+F13)+r2(F21+F23)+r3(F31+F32) |

~iri.Fi=r1(F12+F13)+r2(-F21+F23)+r3(-F31+-F32)

~iri.Fi=(r1-r2).F12+(r1-r3).F13+(r2-r3).F23

| ~iri.Fi=-r12. |

|

r12-r13. |

|

r13-r23. |

|

r23 |

~iri.Fi=U

but steady state implies that

å Ai(t)~å Ai(0)

so that for a large enough t then

2<T>=-<U>

For a relaxed body with a large number of component stars/galaxies, T and U are constant so we don't need to do any time averaging. This permits us to simply write

2T=-U

This is the most useful form of the equation as no time averaging is involved.

2.3.1 The Application and Assumptions of the Virial Theorem

Kinetic Energy

We will assess this in three stages

-

consider a cluster of N visible stars of equal mass M

now in a similar technique to that which is used in Thermodynamics

<v2>=<vx2+vy2+vz2>

<v2>=<vx2>+<vy2>+<vz2>

Þ <v2>=3<vx2>

this is true for a spherical symmetric system

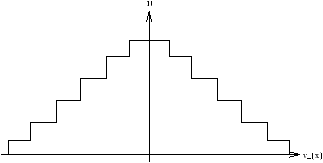

where s is known as the one dimensional velocity dispersion which is the root mean square of vx which also is the standard deviation of the radial velocity relative to the mean.

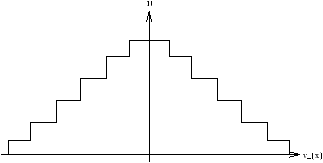

Figure 2.17 - Distribution of the Velocity

- the cluster contains stars with a range of different masses ( m1, m2, ... ), these contribute

| T=T1+T2+... = |

|

s12+ |

|

22+... |

- some of the stars are invisible, however this doesn't change the equation and so it is still

this is because the visible and dark matter mass have the same distributions (an assumption)

Potential Energy

-

Example One:

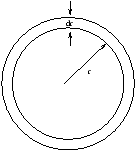

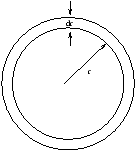

- a sphere of uniform density r , radius R so that the mass is

to compute the potential energy ( U ) we consider assembling in shells where we add shell by shell of thickness dr

Figure 2.18 - Shell Adding to Calculate Potential Energy

however M(<r)=4/3p r3r so

but M2=16p2/9R6r2

if we now apply the Virial Theorem

2T=-U

so all we need to do is observe what s and R is to be able to obtain the mass M

- Example Two:

- via the observations of galaxy clusters (Carlberg et al 1996, Astrophysics Journal 462, 32), in this example we will be looking at galaxy cluster A2390 which has:

s =1093 kms-1

r=4.5Mpc

from the observations of the light profile we can derive the virial mass

the mass in the stars is

a typical value for a galaxy cluster is 60. The scale of this is some large that this is believed to reflect the Universal Value.

Wm=0.3

2.4 Gravitational Lensing

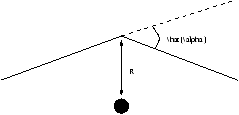

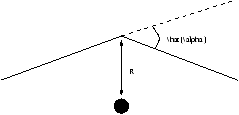

There is really only one equation in this aspect of physics (for the weak gravitational limit, ie. not near a black hole), a photon with an impact parameter of R is deflected through an angle a

this is what Einstein postulated in 1915, it was double the size of the classical value. The weak field is when R>>RS where RS is the Schwarzchild radius which is

for the Sun RS=3000m and at the Sun's limit a=1.75'' . For all astrophysical objects except a black hole RS<<R

Þ a~ 1''

we can therefore use small angle approximation

sinq=tanq=q

we can treat light as travelling in straight lines which have been bent as it passes an object

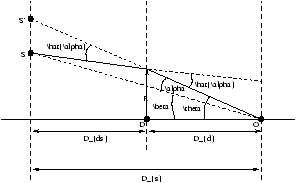

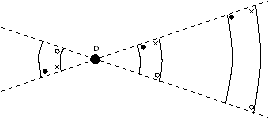

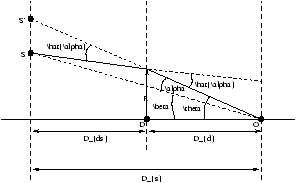

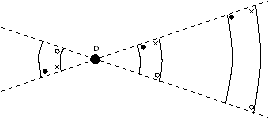

Figure 2.19 - The Basics of Gravitational Lensing

Figure 2.20 - Gravitational Lensing

2.4.1 The Lens Equation

We consider the plane defined by the source S, the deflector D (star/galaxy) and the observer O. The line OS defines the optic axis, the ray from S and going towards O is in the plane SDO. The lens equation is a statement of the geometry

AS=AS'-S'S

Dsb =Dsq -aDds'

We note that normally Ds=Dds+Dd however this is not true at cosmological distances

and these cosmological angular diameter distances relate the transverse distances to their angles.

The lens equation simply says

Figure 2.21 - The Lens Law, Viewing End On (View on the Sky)

the problem is to solve for q (the image position), given b (the source position).

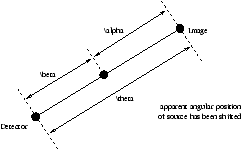

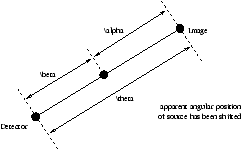

2.4.2 Solution for the Point Mass

we know that

and so we rewrite the lens equation as

however Dds/DdDs=qE2 so

q2-bq -qE2=0

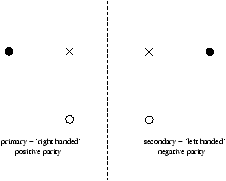

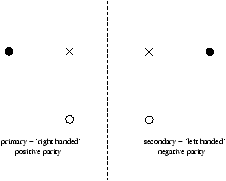

so there are two solutions and two images, this corresponds to one above the optic axis and also there is one below it.

Figure 2.22 - Solutions for the Point Mass

when b =0 then q =±qE and this is for the perfect alignment case which forms a ring image of angular radius qE . This is known as an Einstein Ring.

Figure 2.23 - The Two Solutions as Seen on the Sky

2.4.3 Images and Parity for a Point Mass

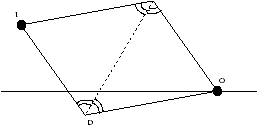

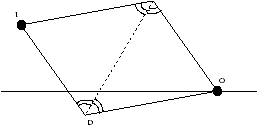

If we consider a source (eg. a galaxy) which has a finite angular size and shape

Figure 2.24 - Images and Parity for a Point Mass as Seen on the Sky

Figure 2.24 shows a series of dots ( · ), empty circles ( ° ) and crosses ( × ), these represent what unique parts of the image form where. This is in accordance with the lens equation.

Figure 2.25 - Primary and Secondary Imaging (Parity)

2.4.4 Magnification

We define the solid angle (the steradian) as:

-

steradian:

- is the angular area l extended

the units of the are (radians)2 (or called steradians)

for example the solid angle of the whole sky is

or another example is a square galaxy with dimensions (ra )× (rb ) then

W =ab

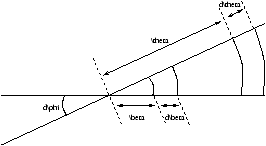

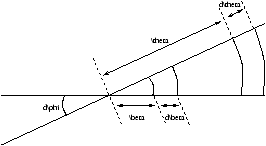

Back to magnification, in lensing the surface brightness is preserved, so lensing magnifies objects (increases their solid angle) so that

(magnification) = (flux amplication)

by using figure 2.25 (redrawn with relevent information as figure 2.27) we can work out the magnification

Figure 2.26 - Calculation of the Magnification

the area of the source is rb df db (here r=DS ) and so the solid angle of the source is b db df . The area of the image is rq df rdq (here r=Dd ) and so the solid angle is q df dq . The magnification is

| M (magnification)= |

|

= |

½

½

½

½ |

|

|

½

½

½

½ |

u=1 Þ M=1.34

u=0 Þ M=¥

[u=0.8266 Þ M=1.5]

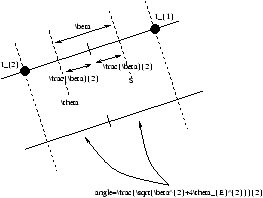

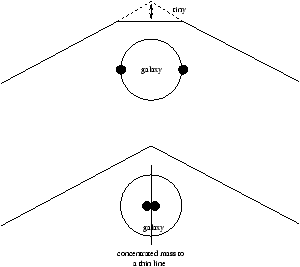

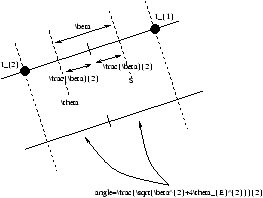

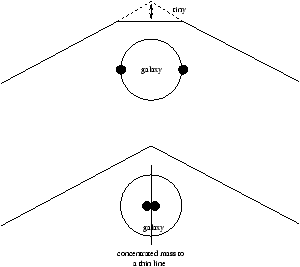

2.4.5 Solution for Extended, Circular Symmetric Masses and Young Diagrams

For a galaxy we can use the thin lens approximation, this is because Ds (etc)>>rgalaxy .

Figure 2.27 - The

Thin Lens Approximation for a Galaxy

We now need to calculate a(q ) due to the projected mass distribution. If the projected mass distribution is circularly symmetric then we only need to consider M(<R) to be concentrated to a point ( R=0 ) and then ignore M(>R) . Therefore

then we apply the lens equation

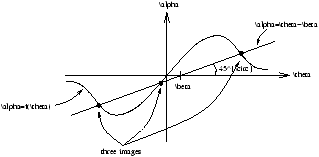

however this is a non-linear equation. So to solve this we use a graphical technique by writing that there are two relations between a and q

-

a =q -b

- a =4GM(<q )Dds/c2DdDsq=f(q )

Figure 2.28 - The Young Diagram - The Graphical Solution