Chapter 4 The Fundemental Law

4.1 Combined First and Second Laws

dU=d-6mu'26 Q-d-6mu'26 W

d-6mu'26£ TdS

or for a reversible process

d-6mu'26 =TdS

d-6mu'26 W£ PdV

or for a reversible process

d-6mu'26 W=PdV

For reversible processes we therefore have

dU=TdS-PdV (4.1)

This is the fundamental equation of thermodynamics

However this equation now depends on state functions only (so there is no Q or W ). It describes the relationship between state variables at neighbouring equilibrium points. So it is independent of whether we move between those points by a reversible or irreversible process.

4.2 Mathematical Structure

dU=TdS-PdV

U=U(S,V)

| Þ dU= |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

dS+ |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

dV |

| T= |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

, P=- |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

| |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

= |

|

= |

|

=- |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

|

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

=- |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

(4.2) |

4.2.1 An Example

S=S(U,V)

| |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

= |

|

, |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

= |

|

4.3 Internal Energy

Given the equation of state (eg. Van der Waal's) what can we say about U(T,V)?

dU=TdS-PdV

we want U=U(T,V) so let S=S(T,V)

| Þ dS= |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

dT+ |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

dV |

| dU=T |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

dT+ |

é

ê

ê

ê

ê

ê

ë |

T |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

-P |

ù

ú

ú

ú

ú

ú

û |

dV |

| dU= |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

dT+ |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

dV |

|

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

=T |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

(4.3) |

|

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

=T |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

-P (4.4) |

| |

|

(equation 4.3)= |

|

(equation 4.4) |

| T |

|

= |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

+T |

|

- |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

|

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

=T |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

-P (4.5) |

4.3.1 An Ideal Gas

P=NkT/V so equation 4.5 gives

therefore as expected U=U(T) .

4.3.2 A Van der Waals Gas

now we insert into equation 4.5

| |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

=T |

|

-P=P+a |

|

-P (using the equation of state) |

4.3.3 An Application - Temperature Change in Free Expansion

V0® V1 in adiabatic free expansion and so there is no work done ( W ) or heat flow ( Q ) so

D U=0

however T may drop for a Van der Waal's gas.

Let T=T(V,U)

| dT= |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

dV+ |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

dU |

| µJ= |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

=Joule Coefficient |

| |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

=-1 |

| |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

=- |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

=- |

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

(cvdT=d-6mu'26 QV=dU)

or from using the energy equation we obtain

| |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

=- |

|

é

ê

ê

ê

ê

ê

ë |

T |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

-P |

ù

ú

ú

ú

ú

ú

û |

4.4 Entropy from the Fundamental Equation

The Fundamental Equation when rearranged says

so if we know U and P we may get S=S(T,V) . For an ideal gas U=3/2kT for the monotomic case and PV=NkT . We plug these values in an obtain

| Þ S= |

|

NklnT+NklnV+constant |

For the case of a Van der Waal's gas where U=3/2NkT-aN2/V

| dS= |

|

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

NkdT+a |

|

dV |

ö

÷

÷

ø |

+ |

|

dV |

The Entropy (in ??TD??) has no absolute meaning but we can compare entropy changes in Van der Waal's and the Ideal cases.

| (D S)Van der Waals-(D S)ideal=Nkln |

|

-Nkln |

|

| (D S)Van der Waals-(D S)ideal=Nkln |

|

(D S)Van der Waals>(D S)ideal (if V>V0)

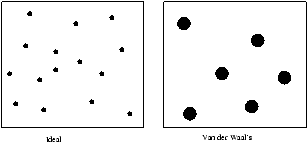

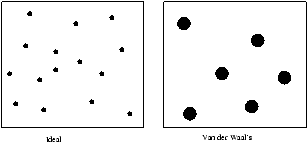

Figure 4.1 - Comparing the Ideal and Van der Waal Case

In the Van der Waal case the molcules occupy a finite volume b whilst in the ideal case the molecules are points. So in an expansion the molecules in the Van der Waal case experience a greater increase in freedom relative to the ideal case.

Þ (D S)Van der Waals>(D S)ideal

4.5 Entropy Max Principle

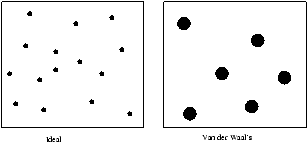

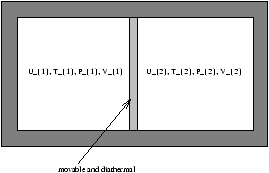

Figure 4.2 - ?????An Experiment?????

What are the equilibrium conditions? We use the Entropy Max Principle:

S=S1+S2 is maximized at equilibrium, subject to fixed U=U1+U2 and V=V1+V2 .

Therefore S is a maximum when dS=0

Þ dS1=-dS2

so when

dU=0Þ dU1=-dU2

dV=0Þ dV1=-dV2

so now the equilibrium condition is

so U1 and V1 are independent variables

T1=T2, P1=P2

so the Entropy Max Principle and the Fundamental Equation of ??TD?? gives us the equilibrium conditions.

4.6 Paramagnetism

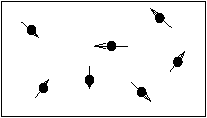

Figure 4.3 - A Box Full of Fixed Particles Each of Which is a Small Magnet

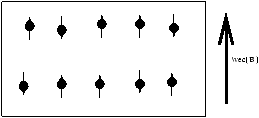

Figure 4.4 - The Box of Magnets Placed in a Magnetic Field

In the presence of a magnetic field the dipoles either align parallel or anti parallel to the magnetic field.

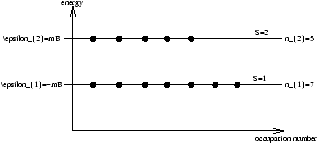

N=n1+n2 dipoles

where n1 is the number of dipoles aligned with B ( e1=-mB ) and n2 is the number of dipoles counter aligned with B ( e2=+mB ).

The total magnetism is

M=m(n1+n2) (M=Nm at t=0)

Total Energy is

U=n1(-mB)+n2(+mB)

® U=-(n1-n2)mB=-MB

The Fundemental Equation (from Electricity and Magnetism first year)

dU=TdS-MdB

as M is extensive and B is intensive this means that B is like -P and M is like V . This is analogous to

d(U+PV)[=H]=TdS+VdP

so U=-MB is analogous to enthalpy H .

We also now need an equation of state

for some constant c at high temperatures.

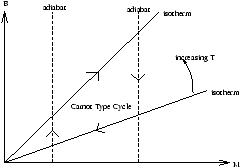

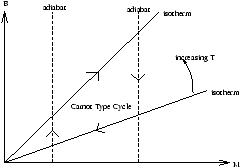

From this we can tell that the isotherms are Mµ B and the adiabats are

dU=0-MdB

-d(UB)=-MdB

-dM.B-MdB=-MdB

Þ M=constant

Figure 4.5 - Isotherms and Adiabats in Magnetism

4.6.1 Entropy

| Þ dS- |

|

dM=- |

|

dM (by Curie's Law) |

We can also derive the energy equation

| Þ |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

=T |

æ

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

ø |

|

-M |

4.7 A Preview of Statistical Mechanics

In Statistical Mechanics we look at the statistics of energy levels to get Thermodynamic information.

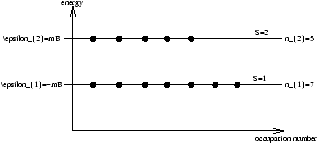

Figure 4.6 - The Model Used in Statistical Mechanics

What are the values of n1 and n2 at equilibrium at a temperature T ?

Statistical Mechanics tells us that the probability of being in level S is proportional to the Boltzmann Distribution.

for some constant Z , to fix Z we use

so we obtain Z=å e-eS/kT normalises the function, Z is called the Partition Function; so

we now compute M and the equation of state becomes

M=m(n1-n2)

Thus the equation of state is

tanhx~ x (for small x)

ie. this is as for Curie's Law (for high T ).

The values of n1 and n2 as T® 0 and T®¥

as T® 0 Þ n1® 1 and n2® 0

so as T®¥ ( kT>>mB ) there is an equal probability of the occupation of 1 or 2. However as T® 0 n1® N and n2® 0 , meaning that the highest probability is in the lowest state.