Chapter 3 The Second Law

Limitations of the First Law:

-

The first law of thermodynamics permits many processes which don't actually happen in nature....why?

-

d-6mu'26 W=PdV

dU=d-6mu'26 Q-dW

d-6mu'26 Q=??

How can we turn d-6mu'26 Q into an exact differential?

3.1 Reversible and Irreversible Processes

A process is reversible if the following two conditions hold:

-

the process must be quasistatic (or so slow that they are always in equalibrium). note that free expansion is not QS and that heat flow across a finite temperature difference is not QS (heat flow is okay if the temperature difference is infinitesimal)

- There must be no dissipative mechanism such as friction, viscosity or electric resistance (since these turn work into heat)

3.2 Heat Engines

Work to heat conversion is easy however turning heat into work is much harder. A device that converts heat into work is called a heat engine. The engine generally has a working substance (eg. gas or steam) that under goes thermodynamic change. The engine generally operates in a cycle which implies

D U=0 (for one cycle)

so from the first law

0=Qin-Qout-W

W=Qin-Qout³ 0

h =1 is perfect efficiency ( Qout=0 and W=Qin ).

h =0 is totally useless ( W=0 ).

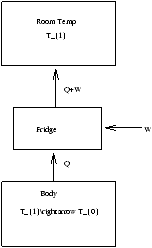

The reverse is a heat pump (aka refrigerator) uses work W to move heat from cold to hot.

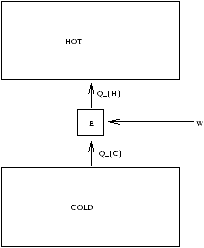

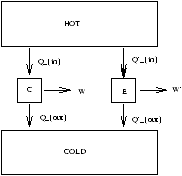

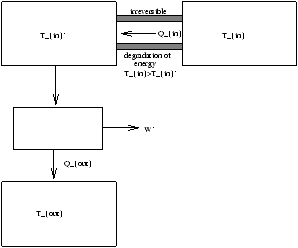

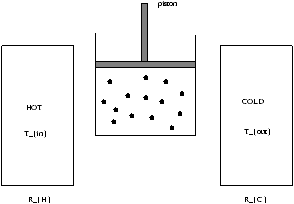

Figure 3.1 - A Refrigerator

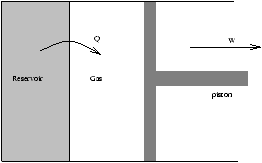

3.3 Carnot Cycle

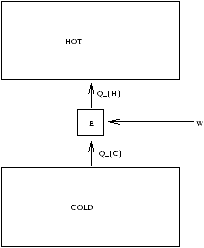

Idealized engine that converts heat into work and is a reversible engine that operates between two temperatures.

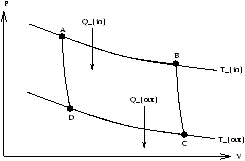

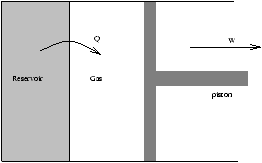

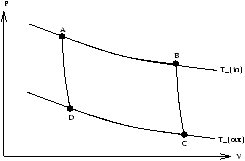

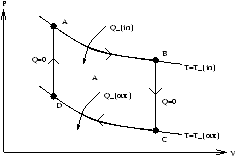

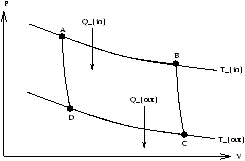

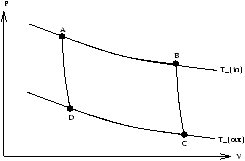

Figure 3.2 - The Carnot Cycle

There are four stages in the Carnot Cycle:

-

-

piston makes contact with RH

- heat Qin flows in

- isothermal expansion

-

-

piston breaks contact with RH ( Q=0 )

- adiabatic expansion

-

-

piston makes contact with RC

- heat Qout flows out

- isothermal compression

-

-

piston breaks contact with RC ( Q=0 )

- adiabatic compression

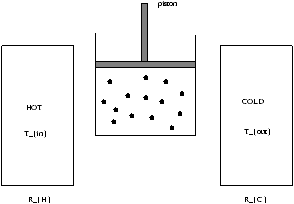

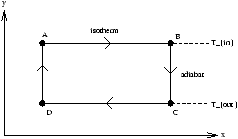

Figure 3.3 -

PV Diagram of the Carnot Cycle

Total work done is the area enclosed A in figure 3.3.

| W=(area under ABC)-(area under CDA)= |

ó

õ |

|

PdV=area enclosed>0 |

3.3.1 Efficiency for an Ideal Gas

-

along the path AB:

-

PV=NkT, U=U(T)=constant

by the first law

d-6mu'26 Q-d-6mu'26 W=dU=0

| QAB= |

ó

õ |

d-6mu'26 W= |

ó

õ |

|

PdV=NkTin |

ó

õ |

|

|

=NkTinln |

|

>0 |

QAB=Qin (see equation 2.2)

- along the path CD:

-

VD<VC

Qout=-QCD

| TV |

|

=constant (see equation 2.20) |

-

AD:

-

- BC:

-

and

Equation 3.2 is the efficiency of a Carnot Engine for an ideal gas. However, h is in fact the same for any working substance. To see this we need the 2nd Law.

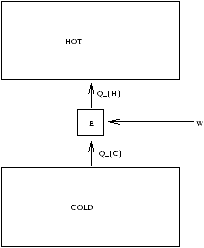

3.4 The 2nd Law

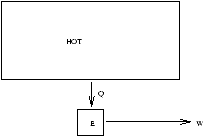

Kelvin Planck's statement is that "no process is possile, operating in a cycle, whose sole effect is the complete conversion of heat into work".

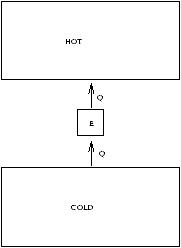

Clausius' statement is that "no process is possible, operating in a cycle, whose sole effect is the transfer of heat from a cooler to a hotter body".

These two statements are logically equivalent

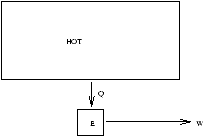

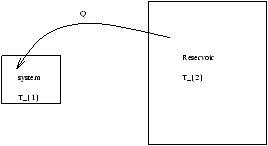

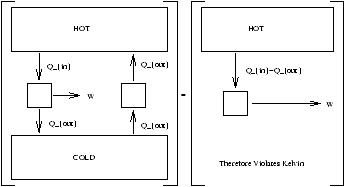

Figure 3.4 - Kelvin's Statement Says This is Impossible

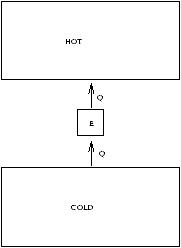

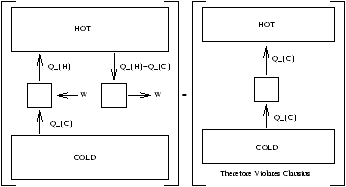

Figure 3.5 - Clausius' Statement Says This is Impossible

The proof of equivalence

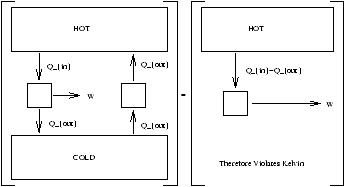

Assume that the Clausius statement is false and so make an engine that violates that statement

Figure 3.6 - Engine that Violates Clausius' Statement

Assume that the Kelvin statement is false and so make an engine that violates that statement

Figure 3.7 - Engine that Violates Kelvin's Statement

If the Kelvin statement is false then the Clausius statement is also false. However vice-versa is also true. Therefore the Kelvin statement is logically equivalent to the Clausius statement.

3.4.1 Carnot's Theorem

"No engine operating between two heat reservoirs can be more efficient than a Carnot Engine (ie. reversible engine)"

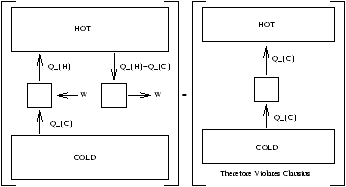

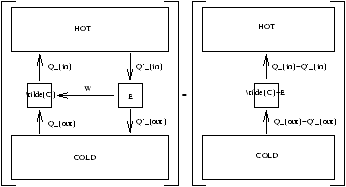

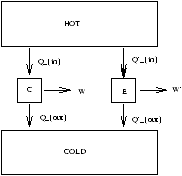

To prove this we let C be the Carnot Engine eficiency h . Let E be the eficiency of another engine. We now show that h '>hc violates the second law, hence h '£hc

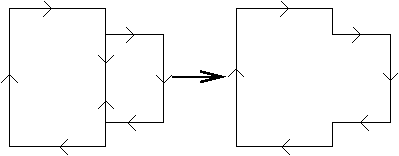

Figure 3.8 - Proof of Carnot's Theorem

W=Qin-Qout

W'=Q'in-Q'out

Now we let W=W' and then

h '>hcÛ Qin>Q'in

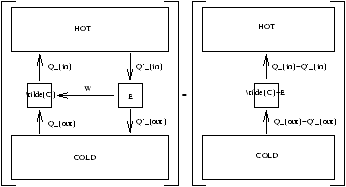

Now we reverse C

Figure 3.9 - Reversing the Carnot Engine in the Proof

C+E moves heat from cold to hot if Qin>Q'in violating the second law.

h '>hcÛ Qin>Q'inÛ Second Law Violated

h '£hcÛ Qin£ Q'inÛ Second Law Okay (3.2)

and hence

h '£hc (3.3)

-

Corollary 1:

- all Carnot Engines have the same efficiency. The proof is if E is also a Carnot Engine may reverse it, and find that hc£h ' . However h '£hc , so

h '=hc (3.4)

- Corollary 2:

- an engine E operating between two temperatures is irreversible if and only if h '<hc . The proof is

-

recall from equation 3.3 that Qin£ Q'in . Is it = or < though? If Qin=Qout then Qout=Q'out may use C to restore the reservoirs to their original state using W after E has operated (so in effect reversing E ) contradictory to irreversibility of E . So E irreversibility must have

Qin<Q'inÞh '<hc

- h '<hc is irreversible (since all Carnot Engines have h '=hc )

so a summary of that

-

h '>hcÛ Second Law Violation

- h '=etacÛ E irreversible

- h '<etacÛ E irreversible

for and engine E between two temperatures. If E operates between more than two temperatures hten h '<etac (see problem sheet 2).

These results are independent of the working substance and of the type of work done.

So there are two important consequences (sections 3.5 and ??3.6??)

3.5 Thermodynamic Temperature Scale

this is true for all Carnot Engines. For an ideal gas Carnot Engine then

This means we can define temperature by

for some T0 . It is independent of working substance and coincedes with the ideal gas scale.

We now have

3.6 Clausius' Theorem

The second consequence of Carnot's Theorem is the existence of a new function of state, the entropy S .

We recall that

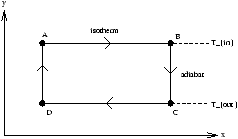

Figure 3.10 - Carnot Engine

Qin=QAB, Qout=-QCD

we have

this is consistent with

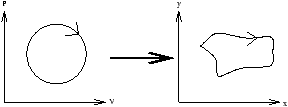

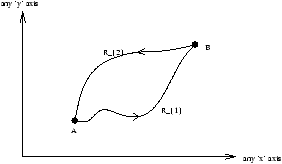

we can prove that equation 3.7 is true for any closed reversible loop, by breaking it up into many smaller Carnot cycles.

So we have to now change the coordinates

| x=PV |

|

=constant on adiabats |

y=PV=constant on isotherms

Figure 3.11 - A Carnot Cycle in the

xy Plane

any rectangle in xy space is a Carnot cycle.

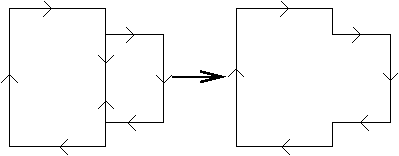

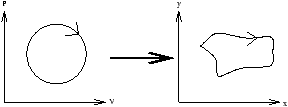

Figure 3.12 - An Arbitrary Cycle in the

xy Plane

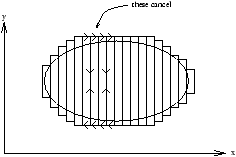

Figure 3.13 - Approximating an Arbitrary Cycle as Many Carnot Cycles

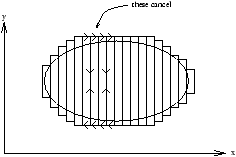

However in figure 3.13 the lines inside the cycle cancel one another out

Figure 3.14 - Lines Inside the Cycle Cancel

These diagrams show that

this becomes exact as the number of carnot cycles used approaches infinity. So this proves that

| |

|

=0 (for any closed reversible path) |

3.6.1 An Example

Take, in the Carnot Cycle, A to B to be free expansion, therefore Qin=0

3.7 Entropy

We recall udx+vdy is exact which means

-

udx+vdy=df

- ò (udx+vdy) is independent of path

- (udx+vdy)=0 for any closed loop

Clasius says that

for any reversible path, so there exists a new function of state such that

S is this new state function called Entropy and we calculate its change by

along a reversible path.

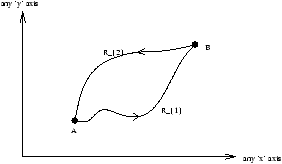

For an irreversible path

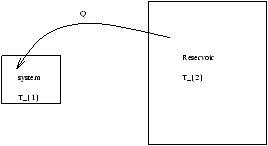

Figure 3.15 - Entropy on Irreversible Paths

the path R is defined as path R1 followed by path R2 where path R1 is irreversible whilst path R2 is reversible.

where R2 is the reverse of path R2 .

however òR2d-6mu'26 Q/T si reversible and so therefore d-6mu'26 Q=TdS

Infinitesimally d-6mu'26 Q/T<dS for irreversible paths

d-6mu'26 Q£ TdS (3.10)

note that d-6mu'26 Q=TdS only if the path is reversible.

For a thermally isolated system d-6mu'26 Q=0 and so

dS³ 0 (3.11)

This is the Principle of Entropy Increase. Entropy of a thermally isolated system increases during an irreversible process and is unchanged for reversible ones. Note that entropy of a non-isolated system may decrease.

3.8 Entropy Changes

3.8.1 Isothermal Expansion For An Ideal Gas

Figure 3.16 - Isothermal Expansion For An Ideal Gas

From the first law

dU=d-6mu'26 Q-d-6mu'26 W

U=U(T)=constant (for an ideal gas)

| (D S)reservoir=- |

|

=-Nkln |

|

<0 |

(D S)total=(D S)reservoir+(D S)gas

this is because S is extensive

(D S)total=0

this is expected for a reversible process

3.8.2 Quasistatic Adiabatic Expansion

as the process is reversible

d-6mu'26 Q=0

so

again as expected

3.8.3 Adiabatic Free Expansion

There is now no reservoir so d-6mu'26 Q=0 . However the process is irreversible so we cannot use d-6mu'26 Q=TdS . So we instead use the fact that S is a function of state, independent of process, and may let S=S(T,V) . Also for free expansion Tinitial=Tfinal . So the initial and final V and T are the same as in the quasistatic isothermal case and so D S is the same

as expected for an irreversible process.

3.8.4 Heat Flow Across a Finite Temperature Difference

Figure 3.17 - Finite Temperature Difference Experiment

The system heats T1 to T2 an so

| (D S)reservoir= |

ó

õ |

|

=- |

|

=-cv |

|

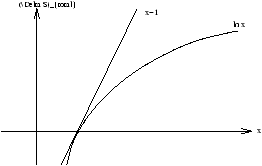

| (D S)total=cv |

é

ê

ê

ë |

ln |

|

-1+ |

|

ù

ú

ú

û |

(D S)total=cv[-lnx-1+x]

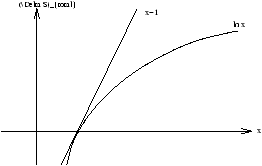

Figure 3.18 - Change of

S Against

x

3.9 Degradation of Energy

The magnitude of D S in an irreversible process is a measure of work that has been wasted. For example in the free expansion case

where W is the work that could have been done if the process were quasistatic isothermal expansion.

Generally, TD S is the energy that becomes unavailable for work as a result of an irreversble process. ie. it is the amount of energy degraded.

D S>0Û irreversible

the size of D S is the work that has been wasted (or lost).

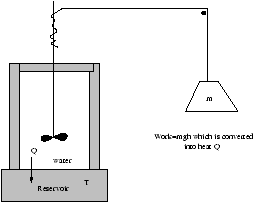

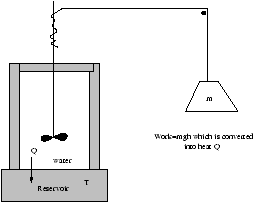

3.9.1 Example of Work Conversion to Heat

Figure 3.19 - Work Conversion to Heat

Q is totally absorbed by the reservoir so the initial state of the water is the same as its inal state.

(D S)water=0

(D S)mass=0

so if we put real numbers into this equation it can give us a feel of wasting work.

M=30kg, h=1m, T=300K, g~ 10, D S=1 JK-1

So for an irreversible process the change in entropy is equal to the amount of work wasted in free expansion

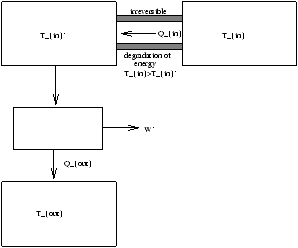

Another example of the degradation of energy, if we recall for the Carnot Cycle

(D S)carnot cycle=0

Figure 3.20 - Carnot Cycle with Heat Degradation

| |

|

=(D S)'resevoir+(D S)resevoir |

W-W'=Tout(D S)

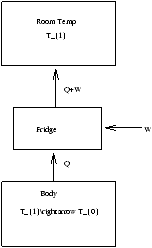

3.10 Application of Entropy - Refrigeration

What is the minimal cost of refrigeration?

Figure 3.21 - Entropy and Refrigeration

We cool a body T1® T0 removing heat Q using work W . What is the minimum W ?

(D S)fridge=0 (cycle)

(D S)body=S0-S1<0

Þ W³ T1(S1-S0)-Q=Wmin (3.13)

This is the minimum cost.

3.11 Recalculation of Carnot Efficency

The existence of S explains why

Figure 3.22 - The Carnot Cycle

| Qin=QAB= |

ó

õ TdS=Tin(SB-SA) |

| Qout=-QCD=- |

ó

õ |

|

TdS=Tout(SC-SD) |

Þ SB=SC

the adiabat DA gives

Þ SA=SD

SB-SA=SC-SD

for any substance.