Chapter 3 Hydrogen - Detailed Structure

The detailed spectrum of the Balmer Series ( n=2 and n=3 in hydrogen) is given on the handout figure 4.1. There is a small deviation from the theory so far, however we have made some assumptions:

-

non-relativistic treatment

- classical electromagnetic field

- nucleus is treated as a point particle

none of these assumptions are true. The proper treatment of these assumptions leads to corrections, in order of importance of the assumptions it is 1 to 3, three being the least important.

3.1 ???

3.1.1 Examples

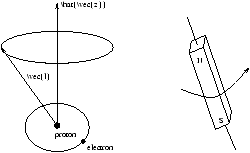

Hydrogen in an externally applied magnetic field (ignoring spin). In the vector model, associated with l is a magnetic moment µl .

Figure 4.1 - ???

µ=IA

by convention we write that

where

|

µB= |

|

(Bohr Magneton) (3.2) |

ge=1

If we apply a static laboratory magnetic field to a gas of such atoms, we choose the magnetic field to be B=Bz

Figure 4.2 - Precession of a Atom (Bar Magnet) in a Magnetic Field

The energy of µ in B is

this technique relies on the relationships between two models

Vector Model Quantum Mechanics

l.z lz

In Perturbation Theory the first order energy shift is

|

D E=<Y |

|

| |

|

l |

z|Y |

|

>= |

|

ml=µBBml (3.3) |

3.2 Relativistic Effects

Bohr's Model states that

for n=1

a is known as the fine structure constant. Since v is much less than c relativistic effects will be small. To include them there are two possibilities

-

do it properly from the ground up by designing a new equation that is really the Schrödinger Equation with relativistic effects included, this is known as the Dirac Equation

- use the Schrödinger Equation and Perturbation Theory to include the relativistic effects as perturbations

we will be exploring the second technique.

3.2.1 Spin

Spin arises naturally in the Dirac Equation. However in non-relativistic Quantum Mechanics it must be treated as a postulate.

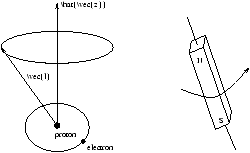

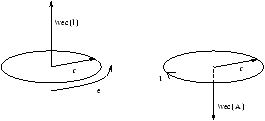

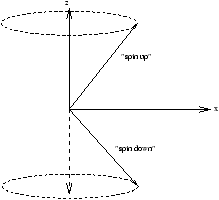

S has only one value, for example S=1/2 but mS±1/2 for an electron.

Figure 4.3 - The Vector Model For Spin

The length of the arrows in figure 4.3 is S(S+1)~ 0.866 . Since spin and orbital angular momentum are independent we write

where Ynlml is the function in real space and cSmS is the spiner in spin space. By the analogy with l

however the Dirac Equation has one more surprise. In non-relativistic Quantum Mechanics gS=2 is a postulate. However in Quantum Electrodynamics gS=2.00232... . For example is says that when compared with orbital angular momentum the spin gives twice as much magnetic moment for a given amount of angular momentum.

3.2.2 Addition of Angular Momentum

When there are two sources of angular momentum these can be added to find the total angular momentum, for example

j=l+s

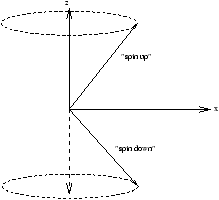

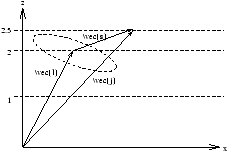

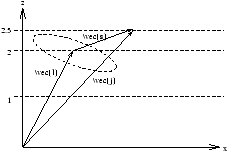

where j is the total angularmomentum, l is the orbital angular momentum and s is the spin. We use the vector model to visulise (for example l=2 , ml=2 , s=1/2 and ms=1/2 )

Figure 4.4 - The Vector Model For Total Angular Momentum

In figure 4.4, if we had drawn s elsewhere on its allowed cone then j would of been different. We can use operator algebra to show that:

we can find the state

You cannot know j , mj , l , ml , s and ms all of these at the same time due to the laws of Quantum Mechanics.

| j= |

|

, |

|

, |

|

, |

|

... Þ mj=j,j-1,j-2,... |

j=l+s,l+s-1,... ,|l-s|

for example j=l±1/2 or j=1/2 if l=0 .

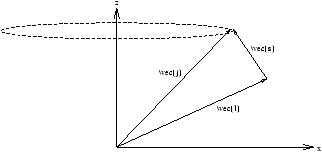

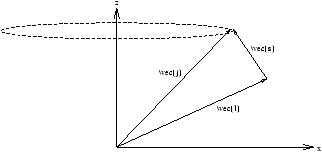

Figure 4.5 - The New Vector Model For Total Angular Momentum

In figure 4.5, the projection of s and l on the z-axis are not known. The Coupled Basis states that we don't know ms and ml .

3.2.3 Spin Orbit Interaction

SEE HANDOUT

E=En+D E

note that En is negative. The energy shifts up for j=3/2 however it shifts down for j=1/2 . When the energy level is high ( j=3/2 ) µs is roughly (symmetric) with µp however when the energy is low ( j=1/2 ) then µs is roughly ¯¯ (antisymmetric) with µp .

Note that:

-

Spectroscopic Notation:

- the states are denoted by the code

(nl)2s+1lj

the general state has s=1/2 , l=0 and j=1/2 then the code is

- Selection Rules:

-

D j=j-j'=0,± 1

D mj=mj-mj'=0,± 1

3.2.4 Other Relativistic Corrections

Two other terms appear in the Dirac Equation

-

relativistic mass correction

- Darwin term, there is no classical picture for this

For example the n=2 level in hydrogen. The extra terms one and two make the spin-orbital more or less the same size but only the spin-orbital term splits 2p3/2 from 2p1/2 (see figure 4.2 ON THE HANDOUT).

Note that the spin orbit splits 2p1/2 away from 2s1/2 however the first and second correction terms together give a shift of 2s1/2 that brings it back to the exact degeneracy of 2p1/2 . The final energy including the fine structure (the result is just quoted)

| Enj=En |

é

ê

ê

ê

ê

ê

ë |

1+ |

|

æ

ç

ç

ç

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

÷

÷

÷

ø |

ù

ú

ú

ú

ú

ú

û |

3.3 Quantum Electrodynamics Effects - Lamb Shift

-

a tiny shift which is bigger for the s states

- biggest for general states but most famous for (2s)2s1/2

- splits 2s1/2 from 2p1/2 , 2s1/2 shifts up in energy by about 1.06Ghz

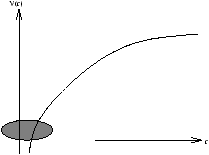

- the electron interacts with zero-point energy of the quantised radiation field. A point like electron is smeared out where its biggest effect on the energy is where dV/dr is at a maximum.

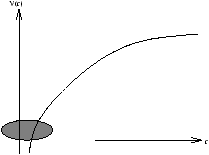

Figure 4.6 - Quantum Electrodynamic Effects

Therefore the biggest effect for the s states is where |Y(0)|2¹ 0 , ie. the s states are smeared out so the electron sits higher in the well (see figure 4.4 ON THE HANDOUT)

3.4 Hyperfine Structure

-

the nucleus is not a point charge

- the nucleus has angular momentum (orbital angular momentum, spin)

this leads to a magnetic moment µI

µI interacts with µj (the total magnetic moment of the electron).

- see spin-orbit as a suitable analogy which leads to very small splittings in hydrogen

- the general solution of hydrogen splits by 1420Mhz ie. l~ 21cm which can be used to make hydrogen lasers (the freqency standard)

This is useful in astrophysics to determine the distribution of hydrogen in space (see figure 4.5 ON THE HANDOUT)

3.5 Isotopic Effects

when m is refered to it is to be replaced by the reduced mass

Different isotopes produce different reduced masses and so the overall scaling of the energy levels is around 0.05% .