Chapter 7 Quantum Statistical Mechanics

7.1 Validity of Classical Statistics

where

mkT~ (D p)2

where l is the themal de Broglie wavelength which is the uncertainity due to thermal and quantum effects.

|

e |

|

~ |

| quantum volume |

|

| volume per particle |

|

(7.1) |

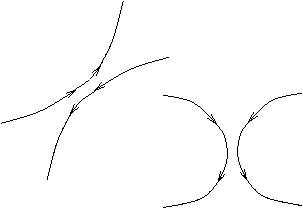

7.2 Identical Particles

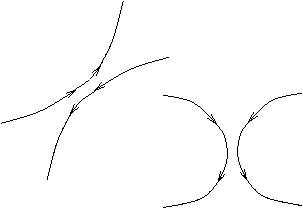

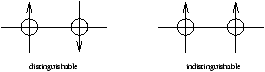

Figure 7.1 - Impossible to Distinguish between Different Particles

In quantum theory fundemental particles are indistinguishable.

Þ |Y (1,2)|2=|Y (2,1)|2

more generally

| Y (1,2)=e |

|

Y (2,1)=e |

|

Y (1,2) |

Y (1,2)=±Y (2,1)

so there are two possible outcomes of this

Y (1,2)=Y (2,1) (7.2)

this (the class is called Bosons) obeys Bose-Einstein Statistics whilst

Y (1,2)=-Y (2,1) (7.3)

obeys Fermi-Dirac Statistics (the class of particles here are called Fermions).

7.2.1 Spin - Statistics Theorem

Particles of 1/2 integer spin are fermons (electrons, protons, neutrons, He3 , ...). Particles of integer spin are bosons (photons, gravitons, W, Z, Higgs, He4 , ...). The He3/4 are made up of other combinations of spin (the proof is in the Atomic Physics's Module).

Points to take note about

-

generally for fermions and bosons, permultations don't change the physical state

- in addition for fermions

Y (1,2)=-Y (2,1)

therefore Y =0 if " 1=2 ", ie if both are in the same state. This is the Pauli Exclusion Principle.

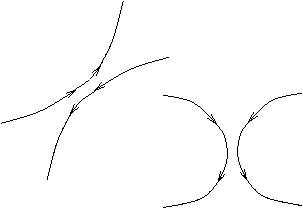

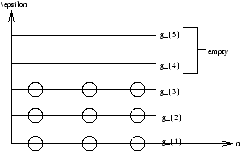

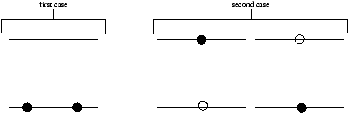

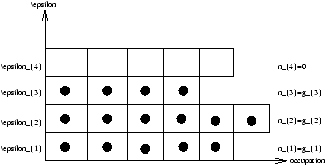

Figure 7.2 - Situations Where We Can Distinguish the Difference

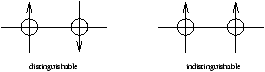

Figure 7.3 - Counting For Two Levels - What is

W ?

For the first case in a classical view W=1 , for the Bose-Einstein case W=1 and for the Fermi-Dirac case W=0 . For the second case in a classical view W=2 , Bose-Einstein its W=1 and the Fermi-Dirac states W=1 .

7.3 Equilibrium Occupation Numbers

7.3.1 The Bose-Einstein Case

we assume that gSnS>>1 and we maximise so that S=klnW is subjected to åSnS=N and åSnSeS=U .

we now consider

we now set df=0 and we obtain the equilibrium values of nS

| f= |

|

[ |

(gSnS)ln(gS+nS)-gS-nS-nSlnnS+nS-ln(gS!) |

] |

+a |

|

nS-b |

|

eSnS |

| df= |

|

[ |

ln(gS+nS)-lnnS+a-b eS |

] |

dnS |

7.3.2 The Fermi-Dirac Case

7.3.3 The Classical Case (Limit)

7.3.4 Interpretations of the Constants

Both a and b are determined by

however in general this is a difficult approach and also we don't introduce a partition function Z .

Instead we consider the condition for S=klnW to be maximised so that

this means that

dS+ka dN-kb dU=0 (at fixed eS)

we now compare this to

dU=TdS-PdV+µ dN

however PdV=0 as eS is a constant

we can now rewrite the following

where there is a minus in the Bose-Einstein case and a plus in the Fermi-Dirac case.

7.4 Fermi-Dirac Gases

As nS approaches gS then the quantum effects start becoming important. The applications of this are

-

electrons in metals

- 3He at low temperatures

- neutron and white dwarf stars

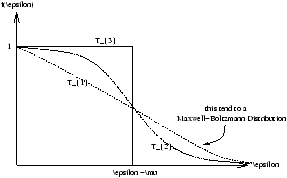

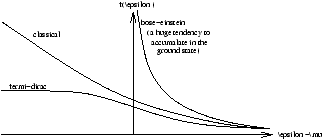

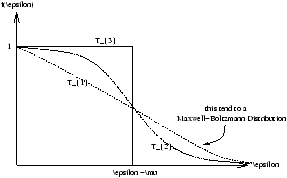

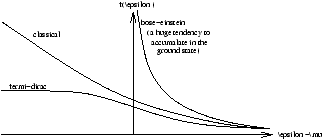

so f(e )=0 if e >µ , f(e )=1/2 if e =µ and f(e )=1 if e <µ .

Figure 7.4 - Plotting the Three Different States of Positioning

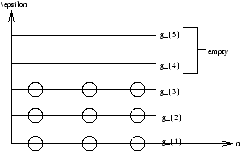

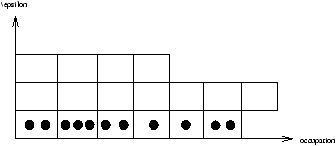

Figure 7.5 - Fermion's Dropping into the Lowest States

e=e (U); µ =µ (T,V)

The properties of f(e ) depend on µ as

f(e )=1 when e <µ f(e )=0 when e >µ (7.8)

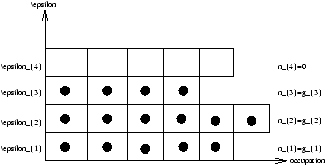

Figure 7.6 - The Fermi-Dirac Ground State

As T® 0 , each particle drops into the lowest possible state, however the exclusion princliple prevents occupation with nS>gS , so each level fills to the maximum nS=gS , then the next energy level fills up to a maximum energy level e =µ . So µ is the energy of the highest occupied state and nS=0 for eS>µ . µ in this context is also called eF which is known as the Fermi Energy.

Figure 7.7 - The Bose-Einstein Ground State

7.4.1 The Calculation of mu (epsilon-F)

Now refering back to equation 7.8 we can obtain

where g(e ) is the degeneracy (from equation 6.25).

In the case of electrons the value of g(e ) has a multiple of two added as an electron can also have two different states of spin.

This equation can be used to calculate µ in terms of N

We define the Fermi temperature by µ =kTF

The Fermi-Dirac effects are important for when T<<TF . For example, electrons in a metal TF~ 70,000K . So Fermi-Dirac statistics are important at room temperature.

where l is the thermal de Broglie wavelength (looked at in section 7.1)

| Þ |

|

~ |

æ

ç

ç

ç

ç

ç

è |

|

ö

÷

÷

÷

÷

÷

ø |

|

=(e |

|

) |

|

Internal Energy

| U= |

|

nSeS~ó

õ |

de f(e )g(e )e = |

ó

õ |

|

de g(e )e =2C× |

ó

õ |

|

dee |

|

|

Þ U= |

|

µ N= |

|

NkTF (at T=0) (7.11) |

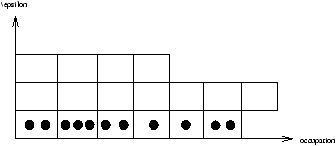

Figure 7.8 - The Exclusion Principle

note that

7.5 Bose-Einstein Condensation

The properties of fS depend on µ (T,V) as T® 0 by using åSnS£ N . As T® 0 we expect all the particles to drop into the lowest energy state s=0 , energy e0 and degeneracy g0=1 .

Þ n0® 0 as T® 0

Þ n1® 0

Þ n2® 0

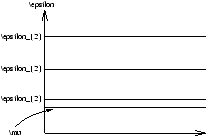

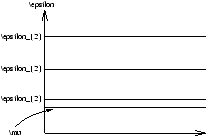

Figure 7.9 - Seperation of Energy Levels

Generally we have

|e0-µ |<<|e1-e0|

for example

If m=He4 , m~ 7× 10-27kg , ~ 10-34Js , we now let L=1cm so that

e~ 10-35J

| µ~ - |

|

, T~ 1K, K~ 10-23JK-1, N~ 1023 |

Þ µ~ -10-46J

this is very small

where in the n0 equation µ is very small whilst in the n1 equation it is not very small, ie. the particles drop into n0 extremely rapidly as T® 0 .

If we compare this to the classical case

For Bose-Einstein Statistics

and because e-µ/kT~ 1+1/N we obtain

| Þ |

|

~ 1023× 10-12~ 1011>>1 at T=1K |

note that

7.6 Photons and Blackbody Radiation

We have seen that

we now consider radiation in a cavity where the energy level is related to the frequency ( e =hn , degeneracy g(e ) ), we compute U

to fix a we use åSnS=N however photons are not conserved in number. This implies that a is zero because this is the Lagrange multiplier for åSnS=N .

what is g(e ) ?

and this becomes

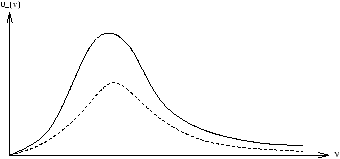

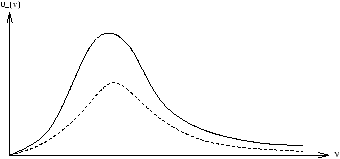

this is known as Planck's Radiation Law

Figure 7.10 - Blackbody Radiation Plot

let x=hn/kT , n=kT/hx

where

and

this is known as Stefan-Boltzmann Radiation Law