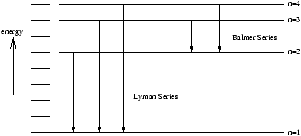

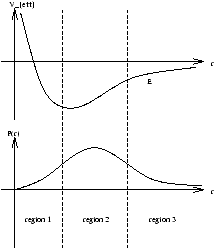

Figure 2.2 - Energy Transistion Levels

|

=R |

æ ç ç è |

|

- |

|

ö ÷ ÷ ø |

(1.1) |

| Þ |

|

= |

|

(1.2) |

| r=n2a0, a0= |

|

(1.4) |

| n = |

|

(1.5) |

| E=T+V= |

|

mev2- |

|

| E=- |

|

hc, R |

|

= |

|

|

|

| D E=E |

|

-E |

|

=hcR |

|

æ ç ç è |

|

- |

|

ö ÷ ÷ ø |

| D E=hn = |

|

| me® m= |

|

|

=R |

æ ç ç è |

|

- |

|

ö ÷ ÷ ø |

= |

|

R |

|

é ê ê ë |

- |

|

Ñ2+V(r) |

ù ú ú û |

Y (r)=EY (r) (1.6) |

| V(r)=V(r)=- |

|

(1.7) |

| Ñ2= |

|

é ê ê ë |

|

æ ç ç è |

r2 |

|

ö ÷ ÷ ø |

+(q ,f ) |

ù ú ú û |

(1.8) |

| (q ,f )= |

|

|

+ |

|

|

æ ç ç è |

sinq |

|

ö ÷ ÷ ø |

(1.9) |

|

|

æ ç ç è |

r2 |

|

R |

ö ÷ ÷ ø |

- |

|

r2+ |

|

r2=- |

|

(q ,f )Y (1.11) |

|

|

æ ç ç è |

r2 |

|

R |

ö ÷ ÷ ø |

+ |

|

- |

|

=c1 (1.12) |

| - |

|

(q ,f )Y=c1 (1.13) |

| - |

|

|

=c2 (1.14) |

|

|

æ ç ç è |

sinq |

|

ö ÷ ÷ ø |

+c1sin2q=c2 (1.15) |

| F = |

|

e |

|

; me=0,± integer (1.16) |

|

é ê ê ë |

(1-e2) |

|

ù ú ú û |

+c1F=0 (1.17) |

| F(e )= |

|

anek (1.18) |

| ak+2= |

é ê ê ë |

|

ù ú ú û |

ak (1.19) |

| - |

|

|

(1.20) |

|

é ê ê ë |

- |

|

|

+Veffective |

ù ú ú û |

P(r)=EP(r) (1.21) |

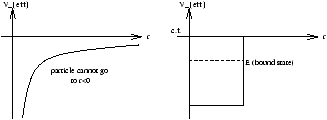

| Veffective=- |

|

+ |

|

(1.22) |

| Veffective=V+ |

|

| r= |

|

| l = |

|

(1.23) |

| a2=- |

|

(1.24) |

|

é ê ê ë |

|

+ |

|

- |

|

- |

|

ù ú ú û |

P(r )=0 (1.25) |

|

é ê ê ë |

|

- |

|

ù ú ú û |

P=0 (1.26) |

|

é ê ê ë |

|

- |

|

ù ú ú û |

(1.27) |

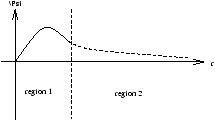

| g(r )= |

|

ckrk |

| P~ | e |

|

rl+1g(r ) (1.28) |

| E=- |

|

| lz=- |

|

| l2=-2 |

é ê ê ë |

|

|

æ ç ç è |

sinq |

|

ö ÷ ÷ ø |

+ |

|

|

ù ú ú û |

| l | 2Y |

|

=l(l+1)2Y |

|

, l=0,1,2,... |

| l | zY |

|

=Ml Y |

|

, Ml=l,l-1,l-2,... ,-l |